Susan Cerulean's memoir, I Have Been Assigned the Single Bird, moved me deeply. The way she combined and intertwined her father's long journey into dementia with our earth's similar long journey into ecological disaster is so exquisitely achieved.

Susan is an Environmental Educator who lives near beautiful Apalachicola on the northern coast of Florida. She is a volunteer steward of wild birds near her home and sees first hand how the human race is decimating not only our birds but so many of all of our planet's other species. "I was left alone with the little birds tracks, the creature carried so little weight.

Its prints were whispers in the sand. I felt deeply happy to experience a short window into a plover's life and to sit quietly near the rare birds I loved so much. To witness, be present. This is my sacred profession: to be with the birds and then tell their stories."

"I'm looking for ways not to despair," Susan's dear father tells her as his mind starts to desert him and he tries to deal with his new reality, his new life.

These two stories are both filled with joy and sadness, humor and tragedy but most of all, they are filled with love. A daughter's love for her father and for our world and how she tries so desperately to make things right, for each.

Author Terry Tempest Williams praises, "I Have Been Assigned the Single Bird is an elegant memoir of devotion and imagination inviting us, with graceful determination, to extend our compassion and sense of family, to all species on this beautiful, broken planet we call home. This book is an awakening."

Below I ask Susan about who she is, then about her book. In the end is her not surprising take on my time travel question. And if she wouldn't mind, I'd like to accompany her:

Tell me about where you live and why you love it so much.

I have written and edited half a shelf of books based in the Red Hills and Gulf Coastal Lowlands bioregions in north Florida, where I’ve lived for four decades.

The movement of shared water unites these two diverse bioregions. On and in the springs, freshwater lakes and rivers, and the seagrass beds and salt marshes of the Gulf of Mexico, that’s where I immerse myself as often as I can. The watersheds of the Aucilla River to the east

and the Apalachicola to the west embrace both bioregions; we know these creeks and rivers from years of exploring by kayak.

I adore the subtle geographies of the land between the rivers, as well. I like to ride my old bike off road on the north-south boundary between the two bioregions, an ancient shoreline where the land drops from 215 feet above sea level to less than 100 feet.

My husband Jeff and I (and our cat Oakie) divide our time between Tallahassee to the north, and Indian Pass/St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge to the south. St. Vincent is a large uninhabited coastal island, owned by eagles, red wolves and shorebirds.

What’s not to love?

Where were you living when you were 7 years old? Are they fond memories?

When I was seven years old, our family of six had just settled into a ranch-style home in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey. The setting was so typically 1950s. I loved the seasons (there were four of them then, back before climate change), and the rituals my family established within the turn of the year were so precious.

Visiting apple orchards and cider mills, and raking leaves in the fall. Ever-so-traditional winter family holidays with aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandmother, and snow days in January. An abundance of birds, daffodils, and forsythia marked spring. And in summer, we children were encouraged to disappear into our own outside play, and to walk to the public library and school.

Everything wasn’t always wonderful. Adults in our lives drank and smoked, partied and fought, and never explained or interpreted their complicated emotional lives.

Is there a book that changed the way you look at life?

Susan Griffin’s Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. She demonstrated how to speak from the body, from turbulence, and from rage. From passion and from the personal. To be unflinching in one’s gaze. And to take command of language and form.

Do you have a favorite children’s book and what about it makes it so?

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken (1962). I loved the bond between the two young protagonist cousins –bold Bonnie and timid Sylvia, the one protecting the other when the “grown-ups were out of the room.” That spoke to me.

It was hard to find literary girl heroines in the early 60s. This novel combined elements of cozy and adventure and satisfying girl power. The wolves were portrayed as wild and unreasonably ferocious creatures in the story, but you knew they were not the real villains.

Did you have a favorite teacher and are you still in touch with him or her?

I’m grateful for classes I took with Dr. Sheila Ortiz-Taylor (the first Chicana lesbian novelist) at Florida State University.

She taught us the art of keeping commonplace books; for 20 years they have been the basis for my work.

Sheila pushed me to write beyond what I knew. To have a commitment to my private truths. I was late coming to a study of feminist writing. Sheila introduced me to Tillie Olsen, Adrienne Rich, Irena Klepfisz, Muriel Rukeyser and others.

I’ve lost touch with Sheila, but she informs my work every day.

What are the funniest or most embarrassing stories your family tells about you?

A story told about me is tender, funny and humiliating all at the same time. One day, in kindergarten, entranced by and wanting something that was not mine, I slipped a bit of furniture from the classroom doll house into my coat pocket. As my father walked me home from school that day, he noticed the toy I had taken. Immediately, he walked back with me to the school and had me place it directly into the hands of the teacher (and probably apologize). All done very kindly, but I remember the shame.

How did you meet your beloved Jeff?

I met my husband Jeff at a parent/teacher gathering at the very tiny alternative school that his two children and my son attended. He didn’t impress me. I thought he was rude and a bit arrogant--smacking his hand on the table and insisting to the kind-hearted director of the school that the children needed more structured math. But I also noticed he was self-deprecating. He’d introduce himself simply, saying “I work at FSU.” For a couple years I figured he was a janitor on campus. He’d never tell you he’s an award-winning geochemist.

|

| Susan, Jeff and Oakie |

We’ve been great partners in work and life for 23 years. We love hiking, kayaking and trying to understand the processes of nature, especially in the wildernesses of Montana, Utah, and North Florida. His left brain complements my right.

Is there a song that you listen to when you are feeling a bit down?

Take Heart by Velma Frye and Eve’s Longing by Becky Reardon can lift me up on a hard day.

How are you different now than you were in your 20’s?

In my early 20s, I was untethered and emotionally undone by the sudden death of my mother, who had suffered from depression for many years. After college, I was lucky to fall in with a group of naturalists; we all worked at the Savannah River Ecology Lab in South Carolina. Together we immersed in the wild places of the southeastern United States. I studied bird and botany books; fished and netted shrimp in salt creeks; and processed the venison my boyfriend harvested. I became wild in every sense of the word.

I distracted myself from the unprocessed pain of losing a mother so young by creating the things I needed but couldn’t afford on my small salary as a biological technician. A makeshift family was one of them. Also I ordered Frostline kits and fashioned sleeping bags, down jackets and vests, flannel shirts and rain ponchos for the wilderness adventures I craved.

I didn’t have my own voice yet. I hadn’t found therapy or a spirituality that I could name yet. That’s the difference between me in my 20s and me in my sixties. But even as a young woman, I learned that the wild places mothered me.

I know you are friends with the brilliant Janisse Ray. How did you two meet?

Janisse Ray and I met at a poetry reading in Tallahassee about 1986.

One of the first ways we supported each other was in a writing group we created with two other women when our children were small. We called it the Hungry Mothers’ Writing Circle. We burned to learn the craft of nature writing.

|

Susan and Janisse

|

What inspired you to write this book?

I want so fervently to help reverse the course of extinction of wild birds, of all wildness, from the planet. That’s my deepest prayer and life purpose. What will make that even remotely possible is if WE the humans, adopt this as essential, all of us. It has to be more important than wealth or power or any of the material things we believe we must have. We have to be willing to overturn the corporations and crooked politicians. We can’t wait any longer to restore our relationship with the earth because right now the earth and everyone on it is in real danger. When a society is overcome by greed and pride, there is violence and unnecessary devastation.

When we know how to protect all beings, we will be protecting ourselves. A spiritual revolution is needed if we’re going to confront the environmental challenges that face us. To exclude, consciously or unconsciously, any species from the continuum of existence is to deny a part of ourselves.

Since I’ve been working and writing toward that end all of my adult life, I needed to try a different approach than just writing about the natural world. I needed to help people see through my experiences (which are the same as everyone else’s—with aging parents, especially those with dementia). That is, truly see that we are all one. So my Dad and I agreed to tell our story. How I hope it helps.

How is the dementia of our culture similar to/different from the dementing diseases that affect individual human brains?

Obviously, that’s the story of the whole book! But in addition: they are similar to me in that cognitive abilities that dwindle in the middle stages of this human neurological disease include: memory erasure, the ability to plan for the future, and the capacity for awareness and compassion. Same is true for cultural dementia. Individual dementias are experienced alone, and they are incurable.

Cultural dementia—we have a choice to engage in it, or not. It can be summed up by these words addressed in an open letter to the European Union this summer by Greta Thunberg and fellow climate strikers: “You must stop pretending that we can solve the climate and ecological crisis without treating it as a crisis."

We ourselves feel crazy: we know we are in crisis as a planet, and that our “leaders” are driving us to believe otherwise.

There is the very real possibility that our president is mad--at the very least he represents the pinnacle of narcissism--the focus on the I, me, mine. I need, I want to, I know, I must be worshiped. He and his minions and handlers are completely gutting the regulations that protect our air, water, lands, wildlife and ourselves and our children. If we are paying attention right now, we are observing the playing out of the colonial takeover that began in the 1500s.

Surely, that’s cultural dementia, and it is the absolute opposite of the indigenous mind that inhabited this continent long before our European ancestors appears.

What have you learned about end-of-life care?

How tedious and boring it can be, and how rewarding. Just like the first months of a baby’s life—every task is essential and also seems endless.

And that to be with a person you love as they transition is a great privilege.

And that it’s a health care crisis. Right now, nearly 6 million people are afflicted with Alzheimer’s; by 2050, it’s estimated that number will more than double. Like millions of other American families, my siblings and I were basically plugging the huge holes in the safety net of our health care system—and the absurdly high cost of meaningful care facilities.

And that we should honor health care and hospice workers with dignity and appropriate pay.

And finally, in a short essay…………………………

IF YOU COULD GO BACK IN TIME

to any period from before recorded history to yesterday,

be safe from harm, be rich, poor or in-between, if

appropriate to your choice,

actually experience what it was like to live in that time,

anywhere at all,

meet anyone, if you desire, speak with them, listen to them,

be with them.

When would you go?

Where would you go?

Who would you want to meet?

And most importantly, why do you think you chose this

time?

First Woman

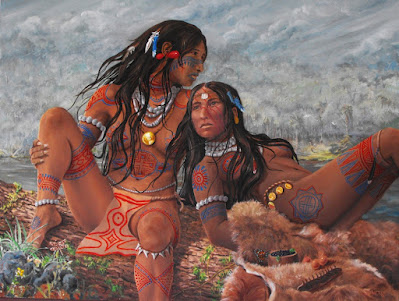

Some years ago, I dreamed about a woman dressed in a ceremonial cape pieced together from the feathers, skins, and bones of wild animals. Her garment was a crazy quilt, fashioned of white beach mouse fur, the plumes of an oystercatcher, the pelage of a fox squirrel, and the bony skull and long bill of a brown pelican, like a helmet. A buffalo skin formed the back of the cloak. Woven throughout were tiny flowers of an endangered plant called butterwort. Bits of ancient clay pottery served as fastening buttons.

I call her First Woman.

I want to travel back to the time and place where she lived, and either be her, live her life, or, learn everything she knows and bring it back here to the present, where God knows, we need it so badly. Specifically, I want to learn how to to respond to our present time with the powerful mind of an uncolonized indigenous elder woman.

First Woman lived two thousand years before the present, when the islands along my north Florida coast were close to their modern positions in Apalachicola Bay: high, wide St. Vincent Island, and to the east, narrow St. George and Dog, swimming like serpents in the sea. Pine forests, scrubby sand ridges, jungley live-oak hammocks, and freshwater ponds, marshes and sloughs covered islands, and sheltered their wildlife.

An abundance of protein—oysters, fish, and shrimp--attracted the Indians of the late Archaic Period (in which First Woman lived), to build camps at the edge of St. Joe and Apalachicola bays. For as long as these islands have existed, people navigated the shellfish-studded lagoons and bays.

I find First Woman and her people at an encampment on the northern shore of St. Joe Bay. I follow her as she forges through the woods. Soft branchlets of southern red cedar brush our faces. We scramble down a 3-foot drop to the edge of the bay. My eyes squint, adjusting to the sudden bright sunlight and the blue gem brilliance of the water, transparent and aglitter in the late morning sun.

People wade with their children in the shallow water to collect horse conches, lightening whelk shells and dozens of other kinds of mollusk. Family members on the beach bash open the shells, and pick out the meat. The shell remains are tossed onto small shell mountains, what we call middens in modern times. Intermingled among the shells that spill from the mound into the bay were deer bones and angular shards of broken pottery. First Woman told me that her people worked only three or four days a week gathering wild foods. The rest of the time was for play, art, exploring, storytelling, and devotion to spiritual practices that kept the ancient stories of the people intact, and kept them connected to the land, each other, and their ancestors. I watched a group of women were teaching their daughters to pray, clustering sunray Venus clamshells in a carefully nested circle.

Meanwhile, men and boys were preparing a set of long dugout cypress canoes for journeying north. First Woman explained that her tribe never stayed near the coast during hurricane season. They’d move back up the rivers and creeks, and some would journey far up the Apalachicola, stopping often to feast and commune with relatives who lived along the river’s corridor.

First Woman’s tribe belonged to a host of aboriginal groups--the Apalachicoli (who gave their name to the River), the Chisca, the Sawokli, the Chatot, the Amacano, the Chine, and the Pacara--remnants of unnamed prehistoric ancestors.

All told, the tenure of the original Floridians familiar with this ground dates back more than 12,000 years on the mainland, 4000 years on the islands--many hundreds of generations. European colonization annihilated the original names, the wisdom and culture, the history and languages of many centuries of vibrant peoples native to our coast have vanished forever.

Still we know that for the first people on this landscape, the coastal terrain was a commons, and movement was on foot or by canoe. Prior to the introduction of agriculture, people shifted between favorite productive locations, harvesting seeds, nuts and fruit during the spring and fall; hunting in the spring and fall. People living almost entirely from wild foods could not—and knew not--to over collect.

First Woman explained the powerful, very particular sense of identity of her people, including how they knew themselves to belong to a very specific, bounded space. The meander of a river, the shine of an island, the drop of a scarp, the sparkle of a large spring--these were territorial markers, signposts of home--during the first 12,000 years of human tenure here. How much different your perspective of a place would be if you knew you lived between an island and the mainland, or between two rivers that you must ford if you wished to leave home. You are here on this side of the water, and through the physical effort of your own body paddling a hollowed-out cypress canoe or even swimming, you cross over and arrive on the opposite shore. Your body participates in the definition of its place.

There was a fire lit in the center of the campsite. Deer meat sizzled in an earthen pan. Around the site I saw reed baskets that contained maize and pumpkin seeds; a variety of pemmican; baskets containing fibrous water lily roots; numerous pots and pans with gourd dippers; and pelts of foxes, otters, and many deer, in various stages of curing.

In one of the huts, I saw little buckskin bags filled with the hair of beaver, soft white feathers, wooden combs, leather shoes, claws of birds and animals, and a thousand other small objects; earth and pigments for body-painting; feather headdresses placed for safekeeping between carefully tied pieces of tree bark, made from feathers of turkeys, cardinals and various other birds. I especially admired hanging baskets of little shells of mother-of-pearl, fish scales, animal bones, and tufts of hair.

These native peoples had created lives from their place, and they knew they belonged there in a way that only indigenous people truly can. They were comprised directly and intimately, cell by cell, of the generosity of land and sea. They lived consciously within an exquisite balance that included human beings. To become animal, not have that division--that's why they wore the skins in ceremony.

As long as humans inhabited this coast, First Woman told me, there was always someone squatting, sitting or walking, paying close attention to the edge. Someone who saw new sand bars emerging, and the nuptials of the herons, and the north and south passages of migratory birds. And eventually, tragically, someone who saw the European sails come tracking over the horizon. I thought of contemporary artist

Theodore Morris, who has created pictorial renderings of Florida's vanished tribes—First Woman and her people. In their expressions, I see their grave concern, knowing that one day the beautiful world they knew would collapse.

I take no comfort as I return to the tumultuous 21st century. But as I think about the long past of our coastline and its uncertain future, First Woman and her cape remind me that in each fragment is the shape of the whole. She also reminds me that my task is to unearth and stitch together what stories and teachings I can. Some of the tales are of impending extinction of land, climate and beings, others simply reflect the beauty and wonder I have seen. The stories may seem fragmented, not smooth and unbroken like the surface of the sea. But maybe this is a true thing, how we live in this time, trying to find our way back to wholeness.

I leave you with one of my favorite passages near the end of this remarkable book:

"As the sun began to angle into the sea, I thought about how our planet and our sun had created such palettes on uncounted nightfalls, long before these plovers or I had come to be. Earth has turned in far lonelier eons, without bird or human. I staggered under a gratitude so weighty that I had to sink to my heels, for I had the privilege to share this time with the creatures I loved."

Thank you Susan for an exquisite book.

Comments