Matthew Quick

Matthew Quick, well-known for his book and film Silver Linings Playbook, has written a new, extraordinary novel, We Are the Light, which has been described as a "journey." That it is, a journey through grief, mourning and unbearable sadness to healing and peace. To rejuvenation and renewal. Read how Lucas and Eli save a whole town after a horrific experience no community should ever endure. That journey is one you, dear reader, definitely want to be a part of.

In a letter to readers of the advance copy of his novel, Matthew Quick writes, "We are the Light encourages all of us to let go and love, even in our darkest hours, and when we ultimately fail, which Lucas Goodgame and all of us will, it bids us to try once more to let go and love--and then again and again and again."

JM: Tell me about where you live and why you love it so much.

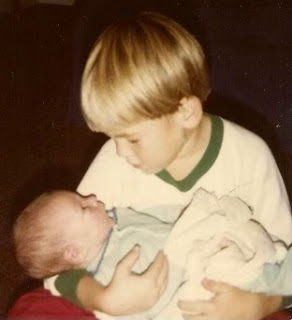

MQ: I currently live on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, right on the Albemarle Sound.

The natural light here is spectacular and healing, which is important for my wife who suffers from Seasonal Affective Disorder. I love that Alicia feels well near the ocean. Whenever we come back from a trip off island, just as soon as we cross one of the bridges to OBX and see the light bouncing off the water like magic, we’re dumbstruck anew. Tourist season can be tough for this introvert. And since Covid reshuffled the deck, tourist season is now pretty much every single minute of the year. But there are still a few places where an introvert can escape from the crowds. Many of the old-school born-here types are warm and lovely. Watching the setting sun slowly drift back and forth along the western horizon of the sound as the seasons and years pass has been a gift. Alicia and I love to sit on our back deck and watch the ospreys divebomb the water and

then carry fish up to nests hidden away in high branches.

|

| The master Kubb player. |

I also love eating lunch at Woo Casa Kitchen.

|

| Sample Woo Casa menu |

And I love how my wife’s face absorbs and then radiates the summer’s glow.

JM: Where were you living when you were 7 years old? Are they fond memories?

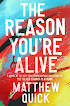

MQ: The years were 1980/1981 and I was living in a small green house in the tiny town of Oaklyn, NJ, which is right across the Delaware River from Center City, Philadelphia.

|

| Seven year old Matthew holding his new baby brother Micah. |

I remember feeling very lonely as a child. I think I was extremely introverted even back then and many of my fondest memories are often devoid of other people:

book in a forgotten corner of the elementary school library during free time, sitting on a bench alone looking at the creek, lying on my back and staring up at clouds, hiding in the lesser-traveled sections of my church, exploring my grandparents’ closets and attic. I never really felt like I belonged. And I often worried there was something wrong with me. I had friends. I played sports. I tried to fit in and mostly succeeded. But I suspected that there was something else I should be doing. It turns out that thing was sitting alone in a room for years and writing novels.

book in a forgotten corner of the elementary school library during free time, sitting on a bench alone looking at the creek, lying on my back and staring up at clouds, hiding in the lesser-traveled sections of my church, exploring my grandparents’ closets and attic. I never really felt like I belonged. And I often worried there was something wrong with me. I had friends. I played sports. I tried to fit in and mostly succeeded. But I suspected that there was something else I should be doing. It turns out that thing was sitting alone in a room for years and writing novels.JM: Is there a book that changed the way you look at life?

MQ: I read Gao Xingjian’s Soul Mountain

when I was doing my Creative Writing MFA, circa 2005. Then I wrote my thesis on his work. He was censored by the Chinese government and ultimately decided to leave China and live in exile. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he talks about the need for ‘cold literature’ or art that doesn’t follow trends and political movements, but is simply the expression of a single individual. It’s been quite some time since I read it, but I remember Soul Mountain being a literal journey into rural China and simultaneously one man’s journey inward. I think maybe what I started to realize while reading Soul Mountain (and all of Gao Xingjian’s work) is that there is sometimes an extraordinary cost for journeying inward and trying to find and then express your true self. Part of that cost is often loneliness or at least solitude. I admire the man greatly.

JM: Do you have a favorite children’s book and what about it makes it so?

MQ: The Monster at the End of This Book: Starring Lovable, Furry Old Grover by Jon Stone and illustrated by Michael Smollin.

I think even as a child I really appreciated a good perception shift. Also, maybe I intuitively knew—and huge spoiler alert here—that the monster we subconsciously fear most is often the person in the mirror. The Jungian work I have been doing lately teaches me the same message. We can tell ourselves not to turn the metaphorical pages, but inevitably we all must. And the truth is always there waiting.

JM : What are the funniest or most embarrassing stories your family tells about you?

MQ: My father likes to remind me that I refused to wear more than two colors at a time when I was little. One Sunday morning, my mother dressed me in multi-colored plaid pants,  which effectively short-circuited my young brain. According to Dad, when my mother refused to allow me to change into a pair of solid, one-color pants, I ran out back and repeatedly slid knees-first through the grass, knowing full well that Mom would never allow me to wear grass-stained pants to Sunday school. I’ve come to believe that this stunt both infuriated and impressed my father, although I’m sure I caught his wrath the day of.

which effectively short-circuited my young brain. According to Dad, when my mother refused to allow me to change into a pair of solid, one-color pants, I ran out back and repeatedly slid knees-first through the grass, knowing full well that Mom would never allow me to wear grass-stained pants to Sunday school. I’ve come to believe that this stunt both infuriated and impressed my father, although I’m sure I caught his wrath the day of.

There is also one about the seven-year-old Matthew Quick getting caught peeing off the deck of my uncle’s OBX vacation house. Apparently, my parents’ guests didn’t appreciate the tranquility of a thin yellow waterfall.

JM: How did you meet your beloved Alicia? How did your first date go?

MQ: Our paths initially crossed at La Salle University in Philadelphia, where we both studied as undergraduates. The guitarist and singer of the band I was in at the time asked me to be his wingman for a breakfast date he had with one of the new frosh. My future wife had agreed to be the wingwoman for my friend’s date and so—when our friends hit it off and therefore didn’t need us to save them—Alicia and I ended up having our first of thousands of breakfasts together. She was seventeen at the time and I was nineteen. Having scored free tickets via our school paper, The Collegian, we went to see the 1993 movie adaptation of The Three Musketeers at the Ritz Five in Old City, Philadelphia. We must have ridden the Orange Line down from North Philly. I don’t remember much about the film, but the handholding we did during it and the kissing afterward on a cobblestoned street corner felt fated enough for Alicia to keep the free promotional poster we received, which hung in the closet of her childhood bedroom for decades afterward.

Alicia will tell you that I “broke up with” her shortly after our first date, but I do not remember doing this. Having recently been wounded in love, I might have seemed a bit noncommittal at first. But since that 1993 La Salle breakfast, my heart has belonged to only one woman.

|

| Wedding Day! |

JM: Is there a song, person, or group that you listen to when you are feeling a bit down?

MQ: When melancholy, I tend to listen to women who play the piano. (My wife composes music for and plays the piano, but I listen to Alicia’s music when I am feeling anxious, especially on airplanes.) When I’m feeling blue, I often listen to Tory Amos

Silent All These Years; Mother; Pretty Good Year; Icicle; Yes, Anastasia or Regina Spektor

MQ: Late forties Matthew Quick is definitely much less social and much more sober—four plus years of sobriety and counting—than mid-twenties Matthew Quick. I think I’ve grown to accept my introverted stay-at-home nature. I’d rather be sober and in control and in bed by nine thirty PM than drunk and surrounded by people whose words I won’t remember the next day after waking up at four AM completely dehydrated.

I also exercise a lot more, mostly for mental health reasons. And I’m in Jungian analysis instead of pretending like I don’t have mental health problems. The older I get, the more I enjoy films and television shows of the past. My two-man movie club has been on a Bergman run lately. I would never want to be in my twenties again, but I really miss the nineties. On fellow author and friend Nick Butler’s recommendation, Alicia and I have been making our way through the nineties-TV-show Northern Exposure. It feels like going home.

JM: Is there a question no one has ever asked you that you wish they would? Something, perhaps, that people would be surprised to know about you?

MQ: I once felt overwhelmingly called to be a minister, especially in my late teens. Not sure why that’s coming to mind now. I remember in my mid-twenties inviting a Presbyterian preacher into my home to discuss the possibility of my entering into the religious life.

But when he put his hand on my head and prayed, I felt repulsed. It was an intense and loaded feeling. The preacher quickly advised me to move in a different direction, saying the religious life was difficult and that it would be hardest on my wife, which struck me as a surprising bit of honesty at the time. I haven’t attended a church service in decades. But religion was a huge part of my childhood, which no doubt colors my writing. I miss going to church, but I also simultaneously really don’t want to go to church ever again. There is a mystery there. And I’m not sure I have even begun to understand it.

It was an intense and loaded feeling. The preacher quickly advised me to move in a different direction, saying the religious life was difficult and that it would be hardest on my wife, which struck me as a surprising bit of honesty at the time. I haven’t attended a church service in decades. But religion was a huge part of my childhood, which no doubt colors my writing. I miss going to church, but I also simultaneously really don’t want to go to church ever again. There is a mystery there. And I’m not sure I have even begun to understand it.

JM: You mention having to deal with your anxiety in your opening to your book, can you talk a bit about where that comes from? Did it play a role in helping you visualize Lucas?

MQ: My grandparents grew up poor during the great depression and then both of my grandfathers fought in World War II. I know a lot more about my paternal grandparents than I do about my maternal, but I can safely say that trauma was passed down through the generations on both sides. Growing up, there was always a lot of anxiety about money and politics. There was a lot of Protestant end-of-times religious anxiety too. It’s a hard way to live. And I took all of that very literally when I was a child.

Alcoholism and mental health issues run in my family. My parents—who never drank when I was a kid—got genes and brain software from their moms and dads, which they inadvertently passed on to me.

Historically, I’ve been a fairly anxious person and my anxiety has led to depression in the past. My former dances with alcohol provided much-needed temporary relief but ultimately made things worse as decades passed. Sobriety and Jungian analysis have begun to remedy much of the above, but I still have a lot more work to do.

At the start of the novel, Lucas is dealing with the horrors of his present-tense trauma, but we slowly learn that he also has a trauma history and a very complicated relationship with his mom and dad. Lucas isn’t me and his parents aren’t my parents.

But my own battles definitely informed the writing of Lucas Goodgame.

JM: How do you feel about “Independent Bookstores” and their role in your success?

MQ: I’ve had many incredibly wonderful experiences via indies, but what’s coming to mind now has to do with the local bookshop supporting my better half.

Alicia published her novel, Smile Beach Murder, in May of 2022.

|

| Alicia with her new book. |

|

| Downtown Books |

Jamie billed it as Parapalooza. Local authors were invited to read a few paragraphs from their latest book. Alicia hadn’t published a novel in a decade. She was nervous as we drove to downtown Manteo, where the event took place. Jamie lined up a half-dozen authors in a newly constructed courtyard and then a small crowd gathered to stand and observe. As I watched and listened to authors of all ages proudly read from their novels and picture books and in one case a deceased spouse’s secret poetry stash, I was struck by how captivated the audience was. Everyone was standing—on concrete—for an hour, listening respectfully in 2021 to writers doing nothing more than reading aloud. People applauded generously. They did not seem restless. They were not looking at their phones. They seemed fully present and glad to be listening to local authors read on a Saturday morning. Shortly after the event began, I got a good tingling sensation in my body that reminded me of when I used to be a teacher of literature and my young students were fully participating—when they were supporting each other not for grades, but because they really were starting to believe in the necessary and transformative power of the written word. Alicia read well enough to send a few people scurrying directly to Downtown Books, where they preordered Smile Beach Murder.

When the book officially came out, Jamie scheduled several signings with Alicia, which helped catapult Smile Beach Murder onto the SIBA (Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance) bestseller list for four glorious consecutive summer weeks.

It’s tempting to focus on the transactional handselling aspect of the above story. Believe me, we are very grateful for the sales. But that Saturday morning when a small crowd willingly stood on unforgiving concrete for an hour to listen to local writers read—that’s a testament to the true power and beauty of the local bookshop. And I think we need that now more than ever. (Jamie is currently taking preorders for signed copies of We Are the Light. Downtown Books in Manteo is the official provider of signed Matthew Quick novels.)

JM: Jungian analysis plays a major role

in your main character’s life and the storyline of your book and it’s clearly a

big part of your personal life. Using the epistolary style to tell the

narrative was brilliant, was that always your intent?

MQ: When I was

creatively blocked, Alicia suggested—many times—that I write another epistolary

novel. I love writing letters and have had some epic pen-pal exchanges. I’ve

maintained intense and intimate email relationships. Some have spanned decades.

But I balked at Alicia’s suggestion. I felt like I had already done that. I

wasn’t sure about the marketability of an epistolary novel. People/critics had

been snarky about it in the past. And I worried that maybe the format was a

crutch.

But then

years passed and I couldn’t manage to write anything even remotely publishable.

The writer,

Nickolas Butler, seconded Alicia’s suggestion as we tried to tease out my

writer’s block during a phone conversation. If I remember correctly, I had told

him that I could write very long emails and letters to friends, but I’d sit at

the computer unable to complete a single page of fiction. I was desperate at

this point, as it had been multiple years since I had completed anything good.

I was ready to try anything.

Two

questions logically followed: Who was my protagonist? To whom would he be

writing?

At the time,

I was doing three hours a week of intense Jungian analysis. I felt very dependent

on my analyst. I also often felt like I needed more time with him, especially

since we hadn’t yet solved my writer’s block. A small part of me irrationally

feared being abandoned by my analyst. That’s when I thought, What if my protagonist was jettisoned by his

Jungian analyst? What if the letters were my protagonist’s attempt to woo his

analyst back?

Shortly

after asking myself those last two questions, I was happily writing.

JM: Am I correct that you first came up

with the tragedy in a theater idea more than five years ago? How did that first

come about?

MQ: Back in 2014, I did a wonderful speaking/signing event at Ambler, PA’s historic Ambler Theater,

which is pictured on the cover of We Are the Light. I was struck by the almost cathedral-like architecture. There were black-and-white photos hung inside to document its storied history. This wasn’t your modern cookie-cutter chain theater. It felt almost holy to me. A proper storyteller’s church. I made a mental note that night, promising myself that one day I would write a novel about a historic movie theater.

Coincidentally—or

for the Jungians out there, perhaps this is a bit of synchronicity—a few years

later my parents bought a home within walking distance of the Ambler Theater,

where I started to see films whenever I visited. Each time, I remembered my

promise.

Over the

years I wrote many false starts. I couldn’t figure it out, until I realized

that the story wasn’t about the movie house—it was about the people who loved

the movie house. Why does a community need to gaze up at light projected onto a

huge screen? I wanted to answer that question.

JM: You mention that Lucas is trying to

reorient to the feminine in a positive way. Can you explain that a bit more?

MQ: Well, it’s

pretty obvious that Lucas has what Jungians would call a mother complex.

Unfortunately, his mother doesn’t really see him as an independent person, but

as an extension of herself. She also sees his masculinity as a threat and,

therefore, tries to undermine his agency. She wants him to remain a boy

forever. This is developmentally damaging to Lucas when he is younger. Because

of this, Lucas can be particularly—and maybe unconsciously—afraid of women.

As we make

our way deeper into the novel, we see that his wife, Darcy, had done a lot to

repair his relationship to the feminine. She sees him as a full person. She

embraces his masculinity. She treats him as an equal. But when she is taken

away from him, Lucas becomes a bit unmoored and regresses to an earlier mind

frame. This is only further stoked when Sandra Coyle starts making intense

demands before Lucas is psychologically ready to respond to the tragedy. Even

Jill, whom I view as heroic, puts a lot of pressure on Lucas that isn’t

particularly helpful at the start of the novel.

The Jungian

work I have been doing teaches that everyone has both masculine and feminine

inside. So when we become afraid of one side of that coin—or worse yet,

demonize it—we are doing violence to those inner parts of ourselves, which

always makes us unwell.

Lucas’s

strong intimate male friendships—particularly with Isaiah, Eli, and even Karl—really

are medicinal. When Lucas takes on the task of initiating Eli—who is also

struggling with a mother complex—they both begin to process the tragedy and

come to terms with the masculine and feminine parts of themselves and others.

JM: And finally Matthew, the ever popular time travel question:

IF YOU COULD GO BACK IN TIME

to any period from before recorded history to yesterday,

be safe from harm, be rich, poor or in-between, if appropriate to your choice,

actually, experience what it was like to live in that time, anywhere at all,

meet anyone, if you desire, speak with them, listen to them, be with them.

When would you go?

Where would you go?

Who would you want to meet?

And most importantly, why do you think you chose this time?

MQ: When I proudly told my father that I’d sold my first novel, he said he had always wanted to publish a book and then started talking about how he had once dreamed of moving to Boston and pursuing an artistic life. At the time, the comment wounded me. I, of course—perhaps narcissistically—wanted him to celebrate my accomplishment, not wax nostalgically about the roads he hadn’t taken. Back in junior high, I found two guitars in our attic—a six string and a twelve string. Inside the cases was music written in my father’s handwriting. When I asked my mother, she told me Dad used to play and had even once regularly performed for sick children at a hospital. It was like hearing my father was actually an alien from another planet. I had never seen Dad play a musical instrument in my entire life.

|

| Matthew's parents, Doreen and Michael. |

At an event promoting one of my novels, a woman in my signing line handed me letters that my father had written her while they were in college. I didn’t recognize the man who had written the words. It made me realize that my father had once been a very different person before he had been forced by his father to be someone Dad maybe didn’t want to be.

I’ll time travel to 1968 and visit the twenty-year-old college-student version of my father at his alma mater, Albright College. I’ll hold up the paperback copy of Salinger’s Franny and Zooey that I found in my grandparents’ house. I’ll ask Dad about the handwritten notes he had recently scribbled inside while taking a literature class. I’ll ask him to play me a song on his guitar. Maybe we’ll sink a beer or two while listening to the new Simon & Garfunkel album Bookends. Maybe we’ll hum along to the song America. Maybe I’ll tell him I’m going to play the last song on the album, At the Zoo, for my future high school students when we read Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story thirty-some years later.

When the beer kicks in and he finally opens up about his hopes and dreams, I’ll encourage him to move to Massachusetts and write a novel. And when he balks, like he has to in order for me to come into existence just five years down the road, I’ll put a hand on his shoulder and say, “Don’t worry, Dad. I’ll do it for you. In about thirty-six years. We’ll get there. I promise.”

JM: Thank you Matthew, not only for writing such an extraordinary book but also for being so open about yourself and your life. I know We Are the Light will touch many, many lives.

Many thanks to the great Man Martin for his illustrations: https://visitor.r20.

Comments

There is a complexity to Quick's work that I love. He believes "we are the light" but he also knows that we are going to stumble on the way to discovering that fact. And the stumble is part of the process toward finding our humanity and the good in others and ourselves. I have read an advanced copy of We Are The Light and I feel it is Matthew Quick's best work yet.

Thanks for this blog post. I very much enjoyed it and the excellent questions.